- Home

- Alison Rattle

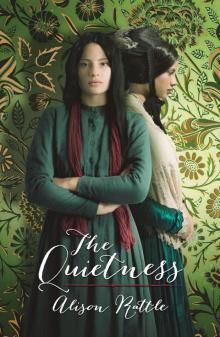

The Quietness

The Quietness Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

London: January, 1870

1. Queenie

2. Ellen

3. Queenie

4. Ellen

5. Queenie

6. Ellen

7. Queenie

8. Ellen

9. Queenie

10. Ellen

11. Queenie

12. Ellen

13. Queenie

14. Ellen

15. Queenie

16. Ellen

17. Queenie

18. Ellen

19. Queenie

20. Ellen

21. Queenie

22. Ellen

23. Queenie

24. Ellen

25. Queenie

26. Ellen

27. Queenie

28. Ellen

29. Queenie

30. Ellen

31. Queenie

32. Ellen

33. Queenie

34. Ellen

35. Queenie

36. Ellen

37. Queenie

38. Ellen

39. Queenie

40. Ellen

41. Queenie

42. Ellen

43. Queenie

44. Ellen

45. Queenie

46. Ellen

47. Queenie

48. Ellen

49. Queenie

50. Ellen

51. Queenie

52. Ellen

53. Queenie

54. Ellen

55. Queenie

56. Ellen

57. Queenie

Epilogue: London, 1884

The Writing of The Quietness: A Note from the Author

Copyright

For my wonderful children, Daisy, Ella and

Riley. Remember it’s never too late to chase your dreams!

And for my Paul. Love you everything. X9

London

January, 1870

1

Queenie

It was a wet day. The rain had turned the roads to sludge. Everyone unlucky enough to be out on the streets hurried past Queenie, without even glancing at the heap of fruit she’d polished to gleaming on her skirts. No matter how hard she shouted, ‘PENNY A LOT, FINE RUSSETS!’ or, ‘EIGHT A PENNY, STUNNING PEARS!’

It was the worst of days. Queenie and Da had been shouting themselves hoarse for hours; Da with his tray of apples strung around his neck and Queenie with a basket of pears balanced on her head. On good days they could easily take two shillings and Mam would buy a bit of bacon and butter to have with their bread, and sometimes they’d have taters, roasted crisp in the fire. But today was different. They hadn’t even made enough pennies for a hot pie and a glass of beer.

Da swore under his breath, ‘Sod this for a trade. How’s a man to wet his bleedin’ throat?’ His face had turned red and Queenie knew his temper would soon be flaring. ‘Come on, my gal,’ he suddenly shouted. ‘If the beggars won’t come to us, we’ll go to them.’

Queenie followed Da down winding alleys while the clouds spilt their innards. The rain had loosened the mud and set free all manner of frights to float down the road. Turds, broken plates and bits of dead dog swirled around her ankles. They stopped outside the gin-shop. A darker, more evil-smelling place Queenie couldn’t imagine. It crouched low on the corner of the road. Its two grimy windows, hung with cobwebs and tattered curtains, were like a pair of blinking eyes staring out at her. She knew she had to go inside or there would be a beating from Da and the taste of blood in her mouth. But it made her guts twist in fright to think of it. It was no good staying on the streets, though. So she lifted up her apron, filled it with pears and pushed open the door with her shoulder.

The room inside was long and low, the floorboards rotten and covered with dirty remains of straw. The air was thick with tobacco smoke and the sour smell of vomit. Customers crowded around the bar drinking; painted women groaned and cursed, and men with red, bloated faces and beady eyes reached out their hands to grab at her flesh.

‘Here’s a pretty one ripe for the plucking,’ said a voice.

Hot breath so close she could taste it.

‘Over here, missy. A penny for a kiss and a feel of your arse.’

A shiny brown penny was lying on the floor. As Queenie bent to pick it up, stubby fingers found their way up her skirt and prodded at her where they shouldn’t. The pears fell from her apron, but the penny was warm in her hand. She stood up and looked around at the leering faces.

‘A PENNY FOR A FEEL OF A RIPE, JUICY ARSE!’ she shouted, and ten minutes later she was back on the street with a handful of coins and the rain cooling the burning of her cheeks.

Back home, when Mam’s face lit up at the sound of coins jingling in her apron pocket, Queenie thought of the groping fingers and how easy it had been to collect a fistful of fat pennies. But as she ate bread still warm and doughy from the baker’s, Queenie could feel the throb of bruises between her legs. She felt deep down dirty. A new kind of dirty that didn’t feel right. She swore she would never let Da force her into one of those places again. She would rather starve. Or take a belting.

Queenie looked around the pokey room she shared with Mam, Da, the little ones and the baby. Seven of them in one room. Seven empty bellies to fill. The little ones like scrawny fledglings with their throats always open, begging for food; crying for a mouthful of sweet bread or the taste of warm fresh milk. There were seven of them to huddle round the stove now that Da had managed to set a meagre fire burning.

‘Fit to warm the backside of ’er Majesty the Queen,’ he pronounced, all la-di-da.

They all sat close; the hot licks of flames brought a blush to the little ones’ sunken cheeks and chased the cold from Queenie’s aching bones. Mam set the tea kettle to boil and when the spurts of steam sailed from the broken spout, Queenie thought of the black funnels of the trains at Waterloo spewing out big, soft feather pillows. She could almost smell the excitement, the oily scent of travel; people arriving and people leaving. She imagined boarding one of those trains one day, carrying a fine leather suitcase and wearing a fancy bonnet, perhaps, and a velvet-trimmed dress. Just like the well-to-do-ladies who sometimes threw a coin from the window of their carriages as they flew by; wheels and horses’ hooves churning up the mud on Blackfriars Road. Queenie could always imagine leaving, but she could never imagine where her journey would end.

Mam handed round mugs of hot water with a spit of tea from the weekly dregs and pulled out her titty from the top of her dress to feed the baby. Mam was forever talking. Klattering on and on, Da would say, speaking so nicely, turning each word out carefully. Like she’d got a mouthful of plums. A mouthful of fat, purple, juicy plums.

‘On account of ’er livin’ with them swanks,’ Da would tease. ‘Got to ’er just in time, I did. Afore she was spoilt goods.’ He’d wink at Queenie but Mam’s face would close up and her klattering would stop, at least until Da had whispered something in her ear and kissed her hard on the lips.

Mam was going on now, telling Da how Gaffy from up the top had gone for his missus again and knocked out the last of her teeth. The little ones were squawking and fighting over a crust of bread.

Queenie closed her eyes and tried to be somewhere else. Anywhere else than in the dingy room she called home; such a dark, damp place, hidden down a passageway in the tangle of streets between Waterloo and London Bridge. The houses were so close together they held each other up. There was no room for the sun to shine down and dry out the wet filth that trickled down the walls and ran through the gutters in front of each doorway. Broken windows were stuffed with brown paper, stinking pools overflowed with shit and slops were emptied from windows. A foul ste

nch hung in the air, clung to clothes and seeped so deep into her skin that Queenie never knew what clean smelt like.

There were bodies everywhere. Men, women and the ghosts of children. The men lounged in doorways, leaned from windows, or slept where they fell drunk in the gutter. There was laughter and wailing, fighting and dirty words. Shouting and squabbling, drinking and smoking. Hollow moans late at night.

Queenie could hear it all now. There was never any quiet with families crowded into every room. Gaffy the cobbler on the first floor, chestnut roasters on the second and Dirty Sal in the back room with her five screaming nippers.

‘Penny for your thoughts, my big gal,’ said Da.

Queenie opened her eyes and looked at him grinning at her, with his arm around Mam’s shoulder, sitting there as though he was lord of the manor. Like Mam and the little ones and a belly full of bread and beer were all he needed in the world to be happy.

‘I ain’t telling you,’ she said. ‘They’re just my thoughts. They belong to me.’

And before Da could say anything else she went to the corner of the room, wrapped her shawl tight around herself and lay down on the pile of straw she shared as a bed with her brothers.

‘Tomorrow,’ she promised herself. ‘Tomorrow will be different.’

She closed her eyes and wished and wished for some quietness.

2

Ellen

‘Mary, not so tight!’ I gasped, as she pulled the laces at the back of my corset. It was a miserable morning, the skies covered in a curtain of fog. The fire that Mary had lit in my bedroom was failing to chase away the cruel, icy draughts that crept through the floorboards and window frames. My arms were dotted in goosebumps and the fresh petticoat that Mary had laid out on the bed for me was already dirtied by a thin layer of greasy soot that had blown down the chimney.

My stomach hurt. The cramps which accompanied my monthly bleed pulled at my insides and the bones in my corset poked spitefully in my ribs. The bell for breakfast rang and I nudged Mary.

‘It’s tight enough, I think. Now hurry with my hair.’ Father couldn’t bear anyone to be late to the table and I did not want to draw on his displeasure. I did not want the morning to be made any more miserable.

The rag I had bloodied in the night was in a dish on my dressing table. Mary finished arranging my hair and covered the dish with a cloth ready to carry it downstairs to Father. He would glance at the contents and make a note in his diary. Then Mary would be dismissed down to the kitchen where she would burn the crimson-stained rag on the fire.

It had always been this way; since that first shocking morning in my twelfth year when I had woken to a dull ache in my back and a slipperiness between my thighs. The blood had soaked through my nightgown and left islands of red on my sheets. I knew it had come from deep inside me and I knew I was dying. It was Mary who found me kneeling by the bed, shivering in terror as I prayed for my life. It was Mary who calmed me and cleaned me with warm, wet cloths and told me I was ‘certainly not dying’, but had merely become a woman. She sat me in my armchair and wrapped me in a shawl and, as she pulled the soiled sheets from the bed and rolled them up, she told me she must inform Father of the event; that he had instructed her to tell him when it happened and that she dared not disobey him no matter how I cried and begged her not to.

Every month since then, I have prayed for the blood not to arrive. Prayed not to feel that weight of shame and hatred when I picture Father examining my dirty secret. Father places great importance on the regularity of a girl’s monthly bleed.

‘It is my duty as your father to see that your menstrual flow is observed with care. Any irregularities can only lead to hysteria, or, in the very worst of cases – insanity.’

Father knows all this because he is an anatomist. An eminent anatomist. He takes his carriage most days to the University College Hospital where he studies the workings of the human body. He has published a book on his findings: Swift’s Compendium of Anatomy. It is a work of great importance. Bound in polished brown leather, its pages are heavy with the secrets of the dead.

On a warm day last spring, not long after I had turned fifteen, Father told me to dress for an outing in his carriage.

‘It is time you were introduced to the world,’ he said.

Mary had been beside herself with excitement and persuaded me to dab some rouge on my cheeks.

‘He’s sure to be taking you to Rotten Row, miss. A ride around Hyde Park to show you off to the gentlemen of town. He’ll be wanting to find you a husband. You mark my words!’ She squealed with delight as she bustled around me fixing my hair and smoothing my skirts. Could it be true? I did not dare to hope so. But I remember I felt as though I was floating and my heart was beating fast, like the heart of a frightened mouse.

Father did not take me to Hyde Park. Father took me to the hospital. He took me down into the dirty yellow light of the dissecting room. Lying on a table was a man. His head was shaven; his skin brown and papery. I stood as though in a trance. Father walked towards the body and picked up a scalpel. I could not look away. He used the scalpel to slice down the centre of the body. Then he pulled it apart and dipped his hands inside. A hot stench of vile sweetness filled my nostrils and my breakfast rose in my throat.

‘Do you have any questions?’ asked Father.

I was dizzy and weak. From behind my lace handkerchief, I managed to ask Father who the man had been.

‘No one of consequence,’ he replied. ‘Just an unclaimed wretch from the asylum.’

I must have fainted then, for I awoke back in the carriage with a damp handkerchief on my forehead. Father was staring at me.

‘It is a pity you were not born a boy,’ he said. ‘You would have appreciated the great service I am doing mankind and be inspired to carry on my good works. As it is, it is enough that you saw it with your own eyes.’

I think Father knows all there is to know about the inner workings of the human body. He knows people from the inside out. I think that was what he was trying to tell me in the sadness of that yellow room. That he knows inside of me. He knows all of me and I can never hide from him.

As soon as Mary had finished my hair, I hurried downstairs to the dining room. Mother was already sitting at the table. She is a wisp of a woman, so pale and fragile that I sometimes think the merest breath of wind could carry her over the rooftops of London and lay her to sleep on a cloud. She was dressed as usual in black silk, trimmed with stiff crepe, her silver hair hidden under a lace cap. I have never known her to wear anything other than black. All my life Mother has been in mourning for her dead babies.

‘Never able to keep one,’ Mary told me once. ‘All of ’em dead before they came out. Poor woman.’ I had looked at her, puzzled, and she had looked back at me with a faraway look in her eyes before suddenly seeing my face.

‘Well, ’cept for you, of course. She was allowed to keep you.’

I often think those dead babies must have taken her love away with them. Bit by bit, one by one, until by the time I came along there was none left for me.

Mother barely nodded her head as I whispered her a good morning. We sat in silence, listening to the shouts of the newspaper boy and the double beat of horses’ hooves that rattled along the road outside. Ninny, the cook, and Mary came into the room and waited at the back for morning prayers to be said. Mary had changed into a clean apron ready to serve breakfast but Ninny had grease spots and smears of bacon fat on her bib. I could hear her breath whistling loudly through her nostrils. She shuffled and sniffed and wiped the sweat from her top lip with the back of her hand.

The dining room door opened at last and Father walked in to take his place at the head of the table. The room held its breath, and even Ninny’s nose-whistling paused, as Father looked at us all with his watery eyes and then bent his head to pray.

Every day it is the same. Ninny retreats from the room as Father’s Amen settles in the air like the soot on the mantelpiece. Mary pours the tea and serv

es the muffins and bacon, while we, the eminent anatomist Dr William Walter Swift, his wife Eliza and I, their daughter Ellen, sit like strangers.

Mother will eat barely a bite before excusing herself and evaporating from the room as though she was never there. She hates the world outside her bedroom. She sits in there day after day, surrounded by fresh flowers and her cages of birds: her finches, parakeets and golden canaries. Her little ‘sugar birds’. I sometimes think she is half bird herself, with her brittle bones and beady eyes.

Father has a hearty appetite, and will eat a whole plate of bacon and a pile of greasy muffins before he folds his newspaper in half and takes out his pocket watch. At precisely half past nine he places the watch back in his pocket and calls for his coat and hat. The front door slams behind him and the ornaments on the sideboard rattle in agitation before the vibrations settle and the house sighs in relief. Then I am left alone in the quietness, with nothing but my books and my dreams of finding love and the emptiness of the day stretching before me.

Except that on this particular morning, Father made an announcement and I somehow knew that my life would never be the same again.

3

Queenie

Queenie was woken by a low moaning noise. She opened her eyes. It was morning, and from her straw bed by the far wall, Queenie could see the baby lying still on the floor, his thin blanket rucked around his middle so his little legs poked out, all dry and bent like twigs. Mam was sitting slumped on the edge of her and Da’s bed, her mouth wide open, and her arms dangling.

Da roared, ‘Shut up, will you!’ and Queenie saw him sitting in the corner of the room, rocking back on his heels. He had that same hard look in his eyes as when he’d been on the beer, and he’d taken his prized neckerchief off and was twisting it round and round in his fingers.

‘Is the baby dead?’ asked Queenie.

Mam started to moan louder. The sound maddened Queenie and she wanted to tell Mam to shut up too. Babies came and went all the time. It had been a weak little scrap anyway, always whining for the titty. And Queenie knew there was another one on the way. There always was. Da had got into the habit of passing Mam his portion of bread again and her cotton gown was pulling tight across her belly. Queenie wanted to ask them why the devil they brought any of them into the world when there was never enough money for them to eat proper, let alone enjoy themselves. But she didn’t. Not with Da in that mood. She just stayed on the straw and let the little ones press close to her.

The Beloved

The Beloved The Madness

The Madness The Quietness

The Quietness V for Violet

V for Violet